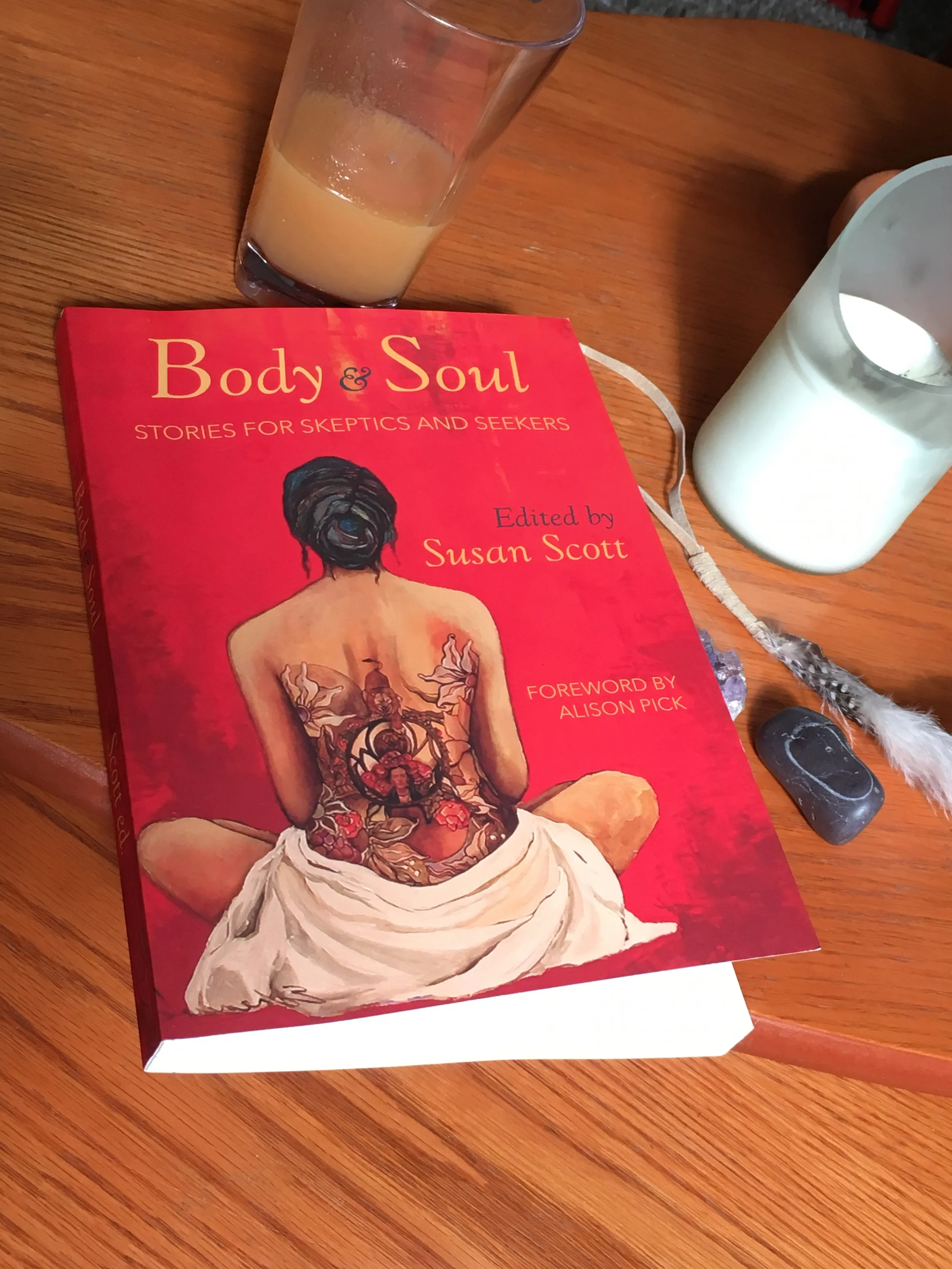

Excerpt from ‘Second Chakra’, Body & Soul Anthology

/A rhythm pulled at me as soon as I entered the park. I’d been doing data entry at my temp job, and I needed something to calm my agitation. Vic stared at me and raised an eyebrow when I told him. I was like an addict hunting for a hit.

Lately, I’d felt the pulse of an internal snare drum insisting on change. It was a constant, trying to keep up with the drum. Keep moving, keep watching, keep marching. This was the pace of the city and this was me, the loyal soldier, trying to find my way. Constant motion, constant beat, constant rhythm. What I couldn’t find was the beat of my own heart. It felt brassy, tight, the drum’s head pulled taut. Keep moving, my head told me. This is how a person progresses. If I put in more effort, if I keep moving, it will all work out.

Thud, thump, trot, march.

Keep the beat.

Snap, pop, click.

That day in the park, I fell constantly, failed repeatedly in Chi Kung practice. “Fall seven times and stand up eight,” the Japanese proverb says. There I was in tree pose, arms extended, legs in a half-squat as if sitting in a chair, thighs gripped, quads burning. My eyes struggled to focus. Time slowed down. My legs wobbled and shook and in an instant they collapsed, knees crackling on the way down. There was a force below the rhythm, an undertow—I was in deep water, feeling the sand give way beneath my feet, not wanting to smash to the ocean floor.

“Go to the ground Pam, focus on your breath," Vic instructed.

So I squatted, hands on the cold earth, and found myself staring at the trees. Something about their rooted detachment forced me to pay attention to the ground beneath me. There was no getting lost in dramatic views or metaphors, my focus was steady: tree bark, roots, green space. The trees themselves were our instructors. Last week we crawled on logs, eyes closed, and I learned that I needed to get down on my hands and knees to move forward, to learn to trust. Our focus had been tested by a woman walking her dog. She didn’t like what she was seeing.

“You crazy sons of bitches,” she shouted. “Take your voodoo movement the hell away from my park. You hear me?”

What did we look like to outsiders? To the city? The trees didn’t seem to mind. Or did they?

My practicing Chi Kung with Vic and the group in Dufferin Grove Park was new, really, only three months old. In the early stages of practice, we did proprioception exercises, sensing the relative position of the body parts during movement. Side to side, back and forth, up and down. Slowing everything down to feel the interconnectedness of breath and movement. The practice was filled with discipline and shifting perspectives, physically and mentally. I was learning how to be present in my body. During these times I started with a head full of ideas, threads of conversations, worries, plans. My breath circulated only in my upper body. Full, deep breaths were elusive. It was difficult to feel my legs or feet. I could only feel the dull, prickly sensation in my chest, as if I were winded. My mind flitted, jolted, from one sensation to the next—cold fingertips, stiff upper back, exhaling from my mouth, a constricted feeling in the chest.

Vic’s instructions were simple, and he gave us small amounts of information about each exercise. Occasionally he would talk about the meridians, the interconnected, internal energetic system, but he kept descriptions brief and encouraged us to focus on the breath in our belly, or the palm of our hands. Over-intellectualizing the process would distract us from the experience of being in our bodies.

“Allow your breath to move into your belly. Find your centre,” he’d repeat, lesson after lesson. “Where your mind goes, your Chi flows. Everything returns to the centre.”

Vic was part spiritual warrior, part five-foot-seven panda in a t-shirt and loose cotton pants. His own experience was the foundation for his teaching. After a car accident years earlier, he’d discovered Chi Kung as part of a therapeutic journey. Vic was direct and honest, with a deep laugh and a soft belly. His observations and insights were astute. He took his time as he led us through exercises, talking about moving from our centre, our Tan Tien, and listening to the internal guidance it provided.

“See the practice as a way of taking you back to who you really are. Teaching you what you already know.”

Something shifted in me as I stayed in the squat position, feeling earth beneath my hands. My breath found new spaces in my torso. The sensation in my heart had dialled down ever so slightly. My mind flitted a little less. I was a smidgeon more aware.

Eventually, I rejoined the others and we began to walk in circles, circling our arms, opening our hearts. I found myself yawning uncontrollably to suck in air. Words circled through my mind—trust, and surrender, and let go. Over and over and over, they circled through, like Vic’s voice. “It’s not about ‘getting’ somewhere, Pam. It’s about process and moving in circles. Let go of your habitual linear thinking and follow the circles. Feel the surrender.”

I would hear these ideas again and again in the six years I worked with Vic but in the beginning they were enigmatic concepts. It would take years of practice to embody—and discover—the meaning of those words.